The inauguration of Donald Trump in January was expected around the world as the turning point for many of the American policies. While issues such as the ballooned government administration were clear domestic problems, a number of policies pertaining to foreign matters had to be addressed as the world was clearly changing.

One of the main points of Trump’s pre-election rhetoric was that a change in US foreign trade would be pursued to influence its balance of trade. The idea was that the import tariffs would both stimulate American production of goods, which would otherwise be imported resulting in increased tax revenue. This would directly ease the worries about the rising debt servicing cost and unemployment. On the other hand, the perceived adverse effect by the countries on the other side of the deal, such as China, India and EU, would motivate those foreign partners to implement Washington favored policies. While there is sound logic behind it, two main questions stand out 7 months after the beginning of his term:

- Have these policies achieved any practical economic impact?

- Have any of the trade partners altered their strategic plans as a result of the implementation or the threat of implementation of any tariffs?

The tariff decision was, to say the least, very controversial. While most analysts opted for solutions close to equal taxation (e.g. Country A charges a 15% tariff on its American goods and the US charges a 10% tariff from it, then the expected US move would be to increase its tariff with 5% to reach the 15% level), the announced numbers of the reciprocal tariffs on the so called “Liberation Day” of May 2, 2025, were vastly different. The published formula, according to which the values were selected, looked complicated. A closer look revealed a fairly simple rationale - the trade deficit for the US with any country is divided by the total goods imports from it and then it is divided by two.

Was that really “reciprocal” as the name suggested? Not really. Reciprocal would mean what was described above - the US charges other countries what they charge the US in the form of tariffs or any other barriers of entry. Instead, the complicated tariff shown by Trump would aim to eliminate America’s goods trade deficit with each country – the result of the existing status quo.

While this argument has its logic in theory, there are broader implications that make the policy questionable.

Tariffs are a market constricting mechanism. There are effects that are surely going to happen and some that may or may not happen. One of the sure shot consequences is the increased domestic prices of the tariffed goods. This would be very counterproductive to Trump’s efforts to curtail the increasing inflation, which had sprung out as a result of Biden’s economy stimulating policies.

On the may or may not side, unfortunately, is the hope that higher prices and lower supply would stimulate domestic production. The reason why this effect is dubious is that goods producing industries require higher capital investments – factories need to be built, workforce trained, supply chains and distribution channels established, etc. For any practical purposes, considering net returns to the business and the cost of capital, no such investments would be made if the expected operation is less than 10 years.

This means that a government policy has to be lucrative enough (sufficiently higher prices) and stable enough (at least 10 years) to attract those investments, which Trump advertised would increase employment across sectors. Additionally, in order to be stable enough, it would require bipartisan support – something which has been increasingly rare in the last 15 years. Considering the case of the tariffs - something that the Democratic party opposed - the possible investors would have to evaluate the chance of the Republicans winning the next elections in 2028 – a highly speculative task given the extremely close margins in the last 3 elections.

Bottomline is that tariffs can stimulate local production, but under certain circumstances, which do not currently exist. As such, the only positive economic effect now is the increased tax revenue – official US data shows that in June 2025 tariff revenues were USD 28 Billion – triple the monthly revenues seen the year prior. Cumulatively speaking, the amount is significant – on August 26 2025, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said that US customs duty revenues may top USD 500 million a year, noticeably altering his previous estimate of USD 300 million a year. Further he added "We had a substantial jump from July to August, and I think we're going to see a bigger jump from August to September… So I think we could be on our way well over half a trillion, maybe towards a trillion-dollar number. This administration, your administration, has made a meaningful dent in the budget deficit."

International trade implications

While US tariffs seem to have a positive effect on the US tax budget, the implications from them extend beyond the economic impact. The intend to use them as a diplomatic tool on the international theatre was declared even during Trump’s election campaign in 2024 and confirmation for that now can be his daily interviews and posts on his Truth social media stating multiple times that if a country wanted access to the US market it would have to agree to specific concessions.

The first major shock was the so called “Liberation Day” on April 2, 2025, and the subsequent tariff rise with China. Markets reacted heavily with a sell-off leading to the SP500 index erasing more than 12% of its value within a week. In a series of tit-for-tat actions since stepping in the office, US tariffs on Chinese goods escalated from 20.7% for 66.7% of the imports to 127.2% for 100% of the imports. The Chinese went from 21.2% on 58.3% US exports to China to 147.6% on 100% of them. The research by Peterson Institute for International Economics shows the development of the US-China tariffs over time ( https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2019/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-date-chart ).

It was clear that such numbers do not make any economic sense and were used purely for their shock value in the hope of influencing the policy makers. According to the recent dataset by Prof. Aswath Damodaran, the Chinese companies operate on average on a 5.68% Pre-tax margin, while the US are at 11.87%. Pre-tax margin is the ratio between the profit from operations and its revenues and is directly affected by the cost of the goods that go in production. Cost of goods sold is generally a big part of the total expense, so increases in the magnitude of 10-20% in COGS have the potential to erase the entire profit. Because of this, further increases in more than an order of magnitude are completely out of any economic logic – whether the inputs for the business increase by 50%, 100%, 200% or even 5,000%, the business will be equally unable to generate profit, which is the sole purpose of its existence in the first place. Hence such announcements can be just for shock appeal.

Shock appeal unfortunately works similarly to bluffs in poker – it is effective only once or twice and more likely with less experienced players. While the US has the biggest stack, China and India are not that far behind – China’s economy is about 2/3 that of the US and India’s economy is about a quarter of the American. These countries have total population of over 8 times that of the US, and their leaders have to find solutions for their people with or without US policies.

Understanding that the other side has some aces in their hand is important in negotiations. It shows clear judgment of the situation and gives the signal that there is a mature person across the table and with some compromise a mutually beneficial agreement could be reached. Announcements of tariffs at insane levels are the opposite.

The latest example is the imposition of an additional 25% tariff on India for purchasing Russian oil for a total of 50% blanket tariff on the country and the most recent threat that China would get a 200% tariff if they do not allow imports of strategically important rare earth supplies.

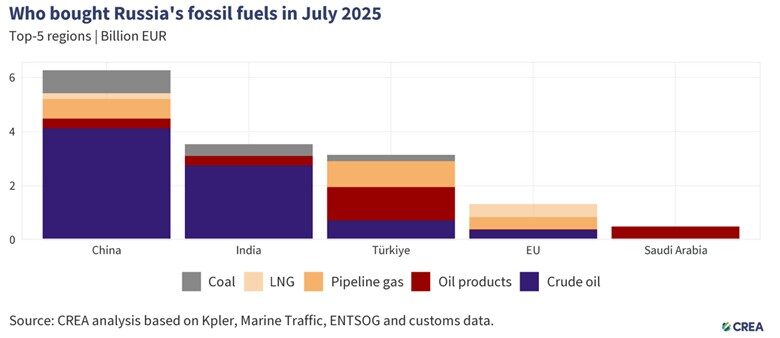

While India does purchase Russian oil, research by the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) for July 2025, shows that the buyers of Russian hydrocarbon products are some of the main US trading partners. Additionally, the companies involved are not private entities, but government owned companies, which shows a conscious decision by these governments to keep the trade with Moscow (https://energyandcleanair.org/july-2025-monthly-analysis-of-russian-fossil-fuel-exports-and-sanctions/ )

The push towards India is clearly not about its trade with Moscow but serving other purposes. India refused to open its agricultural markets to US goods and the move gained significant support in one sector Modi has been lacking – the Indian farmers. This, plus isolating India from the Russian energy markets, all play in the hands of Washington to make both sides weaker.

The push to weaken India has been evident in the US support for Pakistan and Bangladesh. With Pakistan – the immense courtesy of its military leader, the self-proclaimed Field Marshal, Asim Munir on his visit to the US, even though Pakistan has a Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and President Asil Ali Zardari, clearly showing that democratically elected leaders have no decision-making powers in Islamabad. Furthermore, the extension of unprecedented USD 20 Billion loan from the World Bank (where the US has the most significant influence) for climate change policies at a time when the country is running a fiscal deficit (the shortfall between a government's total spending and its total revenue in a given financial year, indicating the government's total borrowing requirement) equivalent to 5.4% of its GDP of USD 373 Billion or exactly USD 20.14 Billion right when the economy is crashing. The level of the trust in the international markets is indicative of the governance there – Pakistan’s government bonds current yield is 12.0070%, which is one of the highest in the world.

Similarly with Bangladesh – various fundings at a time when nearly all major international initiatives were stopped by DOGE for a government led by a person with a title of “Chief Adviser” and who has continuously postponed elections to the point that even its military leader noted the lack of decision and the need for a democratic election.

The push towards China is coming from a position of much less choice. The times when China was a developing economy are gone with its major tech and EV conglomerates covering more markets. Progress in AI, technology and EV will require even more rare earth elements. While a decade ago this trend was mentioned by researchers, now it is clear that stable supply of them will need to be secured to give a chance for the US to retain its position as a tech leader in the world. The problems Washington has is that tech progress outpaces REE supply, Chinese tech companies’ growth is significantly higher than that of US companies and most importantly – China controls over 70% of REE global mining and over 90% of processing, including refining and magnet production.

By chasing the cheapest short-term strategy, US have put themselves in a strategically dangerous position where they rely on the willingness of China to sell such produce to them. Unfortunately for the Trump administration (and at least the next 3 administrations), there is no fast fix. Setting up infrastructure, mining and processing facilities requires massive capital investments and most importantly – time. А place like Afghanistan, which is rich in REE, would require 16 years from the discovery of a deposit to reaching operational status. The estimate, however, is a best-case scenario and requires political stability and presence of adequate infrastructure, both of which a rarely associated with the country. It is a similar situation with a number of African countries, which also have significant REE deposits.

On the contrary, China needs US for significantly shorter-term objectives. US is their main trading partner and considering the higher purchasing ability of the US it would be very hard to replace all trading channels and avoid economic recession.

The results of this high tariff scare strategy are far from what the US pursues. The isolationism by Washington has caused its trading partners to look for opportunities elsewhere. While the Sino-India relationship is complex due to the Chinese incursions in Ladakh, the push for the Doklam plateau, the claim on the entire Arunachal Pradesh and the possible weaponization of the water resources of the Brahmaputra River, the Chinese exports to India in 2025 have grown 14%, to ASEAN countries by 13%, to UK by 8% and EU by 7%. Additionally, such large tariff differences would cause countries with lower tariffs to set facilities, which would import semi-finished goods from high-tariff countries and export finished goods to the US. This has already been happening in ASEAN countries. Additional developments include the trade deal that India signed with the UK, the talks among unlikely partners China, Korea and Japan, Canada’s warming up to trade with ASEAN countries, increased trade between China and Brazil and so on.

While the Trump administration came with the promise for more clarity, 7 months into service, much less of it available. It is increasingly more ambiguous which decision pursues a national objective and which a personal ego boost. Example for the later are the constant reminders by Trump himself for deserving the Nobel Peace Prize by using the access to the US markets as a bargaining chip. Going into absurd lengths by claiming that he was instrumental in the peace between Pakistan and India after Operation Sindoor only to be officially rejected by the MEA of India and Modi himself only made matters worse and put the whole relationship with India under a big question mark. India, on the other hand, has no other alternatives, but to look elsewhere and establish greater presence with other trading partners. It is increasingly evident that others will have to do the same and groupings, such as BRICS and Mercosur will increase their importance.